Historical interpretation of the Tunisian Context

In Tunisia, the revolution has revealed the depth of the gap between the educational system and the country’s economic reality in terms of the inability of the labor market to absorb graduates, and socially, in terms of the inability to socially integrate the younger generation’s victims of marginalization, and politically, in the sense of denying young people participation in public affairs through various organizations, State institutions, especially democratically elected officials.

It is enough to recall that young Tunisians who have joined the hotbeds of tension in Syria, for example, conquer the highest proportions compared to other different nationalities, moreover a significant number of terrorist attacks in Europe were carried out by Tunisians.

Understanding this phenomenon and revealing its circumstances and causes in all its historical, cultural, intellectual, political, and social dimensions remains an urgent goal.

When studying youth’s issues and its cross-cutting topics such as education, employment, civic engagement, the participation in the political life and the importance of social inclusion and the criteria of integration, the relationship with religion as faith, thought, politics and terroristic practice, we can draw a bigger picture of the Tunisian context and its effect on the social contract in general.

Education

When deciding to study the conditions of countries and people in various aspects of life, as well as in cultural, artistic, intellectual, and civilizational aspects, the researcher finds in the educational system and its content, an honest reference, a revealing mirror of today’s reality, and a truthful prophecy about the coming decades, generation after generation.

Whenever education is widespread throughout the country among all layers of society, progress and prosperity will be attained.

Today, education is linked to several important issues related to modern societies, especially in countries that are still seeking growth.

Muhammad Al-Sharafi:

“The Reformer Minister” who had been charged with infidelity by Islamists.

Mohamed Al-Sharafi, a professor of civil law and one of the symbols of the leftist Afaak movement in the sixties and head of the Tunisian League for the Defense of Human Rights, took over the Ministry of Education on April 11, 1989, a year and a half after the “medical” coup of Ben Ali.

Al-Sharafi had a reformist vision for the school, based on its reconciliation with the state and the principles of democracy and human rights.

He considered that education in Tunisia had become a reactionary trend, in contrast to the state’s modernist trend, and that the Tunisian school did not educate children citizenship but rather on ideals and references that contradict that.

Al-Sharafi had put the review of school programs as the first priority. He decided to prepare and print new schoolbooks in few months and withdraw the two books of Islamic education for the fifth and sixth grades and replace them with a book by Mukhtar al-Salami, the Mufti of the Republic at that time, on “ijtihad in Islam”. He found in the two above mentioned books serious implications:

- Like the right of a husband to beat his wife.

- The Khilafah is the only legitimate political system in Islam.

- The punishment for abandoning prayers.

- A list of thinkers whose reading is forbidden,

Al-Sharafi announced this in a press conference in September of 1989 and explained his vision of the school and the seriousness of what he found in the two withdrawn books.

The protest campaign was launched:

- Official Islam against the decisions of the Minister of Education,

- The reaction of the Ennahda movement was strong.

- A statement signed by Abdel-Fattah Mourou, entitled “No to mocking Islam,” was issued accusing Charfi of perpetuating the “Bourguiba’s Project against Islam and the Arabic language” and of “attacking the sanctities and feelings of the nation.”

- Protests with the slogan “There is no god but God and Al-Sharafi is the enemy of God.”

- Al-Nahda considered Al-Sharafi a symbol of what it called “the policy of draining the sources,”

- Violent street protests.

- Protests and strikes in institutes and universities, led by Islamic students, have continued for more than a year.

Laws 1991 and 2002:

Between a legislative translation of the modernizing approach to education and submission to the dictates of loan funds

Muhammad Al-Sharafi oversaw the drafting of a new legal framework that superseded and replaced the 1958 law, Basic Law No. 65 of 1991 relating to the educational system.

The first chapter of it sets thirteen goals for the educational system, including:

- Raising awareness among young people of the Tunisian national identity.

- Developing a civic sense and a sense of civilized belonging at the national, Maghreb, Arab and Islamic levels.

- Strengthening openness to modernity and human civilization.

- Raising young people to be loyal to Tunisia.

- Preparing for a life in which there is no room for any form of discrimination based on gender, social origin, color, or religion.

- Enabling learners to master the Arabic language and at least a foreign language in a way that enables them to have direct access to the production of scientific thought and qualifies them to keep pace with its development and contribute to it.

As the 1991 law enshrined:

- The concept of basic education, which includes in addition to primary education (six years) three years in preparatory schools. This fix has been prepared since the eighties.

- Compulsory basic education between the ages of six and sixteen,

- Adopting Arabic in teaching all human, scientific and technical subjects in primary and middle schools.

Al-Sharafi remained in the ministry until 1994, in order to complete his reform by issuing new textbooks and the necessary applied texts.

Although the 1991 law was less than ten years old, the directive law No. 80-2002 that copied it maintained the same philosophy and principles.

This law was drafted under the supervision of the Minister of Education at the time, Mansour Al Rouissi, who also adopted the left political ideology, but, unlike Mohamed Al-Sharafi, he joined the Ben Ali regime from 1987 until the revolution.

The 2002 law came to keep pace with developments and “international standards” in the field of education, for example adopting the “competencies approach” and focusing on periodic and regular evaluation of all components of school education.

But Al Rouissi reforms also included:

- Changing the formula calculating the baccalaureate rate, allowing a much higher success rate. As a result, the numbers of students in higher education rose without employment prospects.

- Practically and effectively canceled sixth and ninth grades exams (initial and preparatory).

- Maintain the formality of the two exams and limit them to an opportunity to elect the candidates to be directed to the elite institutions.

- Abandon technical schools’ programs.

- On a psychological level, a general feeling of bitterness was born.

The 2002 law still, despite some minor amendments, regulates education in Tunisia.

The failure of the social elevator represented by the public school and the blockage of horizons in front of a large proportion of the graduates were among the most important reasons that led to the 2010-2011 revolution.

Moreover, after the revolution, successive governments were unable to complete a comprehensive education reform.

Employment

After the 1992 Law on Educational Reform and at the beginning of the third millennium, the Tunisian school produces annually, tens of thousands of degree holders. Those who drop out of school and trying to join the job market, find it incompatible, so they strengthen the reserve army of the unemployed and marginalized. Therefore, linked to the educational system, thorny issues of youth employment and the labor market are raised, and embarrassing questions are asked about employment ratio in Tunisia.

According to the numbers of the National Institute of Statistics (INS), the share of the population aged 15 to 29 has remained high and stable, around 28 to 29%, between 1960 and 2010. A downward trend change has occurred from 2010. In 2017, this share fell to 23%. This change in trend heralds the beginning of a lower pressure on the labor market, but this is a process that will take time and will not be continuous. We should even expect a slight return to the transitory rise in the years to come. Indeed, the share of 0–15-year-olds in the total population had already experienced a slight but significant increase: it went from 23 to 24% between 2010 and 2017, a recovery caused by a slim increase in fertility.

There are more low-skilled male workers or self-employed workers in informal jobs. Informal jobs are mainly made up of very small, unstructured enterprises that do not keep accounts, and pay little or no taxes. In sum, in the informal sector, employers do not comply with the main legal requirements relating to workers’ rights, job security and social coverage. Productivity and pay are low. Precarious informal jobs also exist in the formal sector. Data from the National Social Security Fund shows that more than half of workers, especially young people, do not have a written contract and do not benefit from sufficient social coverage – not affiliated to the National Social Security Fund (CNSS) or not even registered. In Tunisia, the size of the informal sector remains large and is even tending to increase. It is well established that the growth of the informal sector results from the gap between the cost of access to the formal sector and the guarantee of formal jobs and the cost of informality. The cost of the formality depends mainly on the requirements and complexity of the regulations, and on the efficiency and integrity of the public administration responsible for enforcing these regulations. The cost of informality results from the exclusion of the benefits of formality (credit, technology, right to public services, etc.) and penalties for non-compliance with the law. In a country where the authority of the State is weak and its steering capacity is reduced, the risk of sanctions is limited, even often zero, and the cost of formality tends to outweigh that of informality.

Civic Engagement

During the colonial period:

Struggle momentum: journalist, sociologist, unionist, and politician.

The first building blocks

French colonization had been settled down due to the corruption and the rising of foreign bank debt, and according to the Bardo Treaty and the Marsa Agreement of May 12, 1881, it resulted in creating a significant popular resistance of varying effectiveness from one side to the other, but it quickly became weak. Perhaps the most important reasons for this are:

- The imbalance of military forces.

- Tribal conflicts and traditional social structure.

- Hostile traditions between the countryside and the city.

- The cut off communication between the authority and the people (the uprising of Ali Bin Ghadhahem in 1864 still feels recent.)

In the face of the failure of the military option, the elites in the cities turned to the option of peaceful resistance within the framework of protection:

- In 1888, Al-Hadhra newspaper was established, and it was the first building block of the creation of public opinion in the Tunisian country.

- In 1896 the Khalduniya organization was established.

- In 1904. Al-Sawab newspaper was published, a weekly scientific, political, and literary newspaper that lasted from April 1, 1904, to 1938.

- 1905 The Association of Old Students of the Sadiqiyah School was formed.

- In the same year, the establishment of the “Tunisian Club” was signed.

- 1907, the young Tunisian youth movement was launched, which expresses the will in the face of the colonizer, and it:

- Considers itself a continuation of the reform movement announced, prior to protection, by Khaireddine Pasha, Ahmed Ibn Abi Al-Dhiaf and Mohamed Bayrem Al-Tounssi.

- It is also considered the first building block of a national political action.

During this period prior to the first world war (1914-1918), several new cultural activities continued to emerge, along with multiple headlines that contributed greatly to the development of a political awareness among readers and played an important role in the initiation of a cultural life.

Perhaps the most important event was the beginning of the consolidation of theatre in Tunisian artistic and cultural spaces, with the emergence of Tunisian theatre groups, as well as the hosting in Egypt of groups of masters like the Soliman Caradahi Choir, who stayed in Tunisia for a few years, as well as the Salama Hegazi Choir.

Clubs and youth associations have also begun to emerge, especially sports teams in various fields, more specifically in football.

In 1906, the first sports association created was the “Football Club of Tunisia”, which soon changed its name to “Racing Tunisia” racing club in Tunisia…

In November 1907, the first official competition (tournament) was organized with only five teams: “Tunisian Football Racing Club”, the “Football Club” and the “Sports Club”, along with two other teams: the Carnot Institute and the Sadiq Institute.

The Glorious Thirties:

After the end of the First World War, following the change in global and internal situations, there was a development in the conduct of elites, a diversity of activities, an expansion of radiation and maturity of national awareness.

In the glorious 1930s, Tunisian society experienced a new dynamic, driven by the creative spirit and the wind of creativity and renewal. The growth of the cultural movement, the proliferation of collective work, such as the emergence of the scout movement, the flourishing of newspapers, the diversity of newspapers and the embracement of a new literary movement, was seen in the poetry of Abu-Kacem Al-shabby, which was not so much a single phenomenon but rather the leader of the innovators. So was Ali Al-Du’aji, in the Art of novels. Also, music and the singing arts had found in Al-Rashidya the best place to flourish.

As for the great reformer and thinker, Taher al-Haddad, he had a pioneering contribution in founding of the General Confederation of Tunisian Workers, accompanied by Muhammad Ali al-Hami and Belkacem al-Ayari. On the issue of women, a wide path was opened for Tunisian women and Tunisian society with the emergence of the Personal Status Code.

Indeed, there is no space left in cultural life in general, literary, artistic, social, political, and intellectual life that is untouched by the spirit of the modern age.

In the mid-1920s, Tunisian sports associations such as “Espérance Sportive de Tunis”, the “Club Africain” the “Club Sportif de Sfax” and the “Etoile Sportive du Sahel” emerged. And behind the establishment of these associations was an elite of patriotic youth who aimed to establish these associations to frame Tunisian youth and rehabilitate them on the physical, psychological, and national levels.

All of this and others were in a relationship of influence on unionism and political activity, as the Tunisian Constitutional Party and the Tunisian Communist Party were founded during (1919-1920) and then the General Confederation of Tunisian Workers had been risen in 1924-1925.The New Constitutional Liberal Party then came in 1934.

Rising from the ashes of dark centuries, Tunisian society has demonstrated a new consciousness, vitality, a freedom-looking spirit, and a strong patriotism, and has set for itself an increasingly militant cultural, youth, social, and political course.

The decade of resolution: 1945-1955:

And after the end of the Second World War (1939-1945), and following the change of the global and internal circumstances:

- Impunity of initiative from the old colonial powers.

- The weakness of old Europe to the power of the rising USA.

- The emergence of a socialist camp supportive of oppressed peoples and anti-colonialist

- The emergence of the international community with new values (human rights) and support for the right of peoples of self-determination.

In the Shadow of the National State: Muting.

The country’s independence process was carried out by the Liberal Constitutional Party, which led the national militant movement. Therefore, accounted solely for all the decisions and measures, and in a useful summary, the matter led to:

State Party Building and State Party Restructuring.

Disagreements broke out from the very beginning of negotiations with the French authorities in November 1953 and the tripartite commissions to disarm the Resistance.

- The dispute started between Ben Youssouf and Bourguiba.

- The assassination of the armed elements and groups loyal to the position of the leader Saleh bin Youssef.

- The 1962 coup attempt (group of Lazhar Al-Sharaiti).

- Repressing the press: Restricting independent newspapers, censoring a number of issued publications. The transfer of Ben Yahmed’s “Afrique Action” newspaper from Tunisia to France, where it continued to be published under the title: Jeune Afrique.

- Dissolution of the Tunisian Communist Party.

- Dissolving the Tunisian Union (USTT) since 1956 and continuing to restrict its Secretary-General Hassan El Saadawi in means of living and in his freedom in daily life until he died in a detention center by a heart attack in 1963.

- The beginning of disputes within the General Union of Tunisian Students between those who accept the intervention of the ruling party in the affairs of the organization.

After the revolution: The waterfall

The 2011 revolution ended the era of censorship and repression of all types and activities of civic engagement. And as soon as the Decree No. 2011-88 dated September 24, 2011, related to the organization of associations was issued, the number of NGOs exploded significantly.

At the end of 2017, more than 18,000 non-governmental organization were counted, most of which were established after the revolution.

In the words of Kamal Jendoubi, former minister to the Prime Minister in charge of relations with constitutional bodies and civil society:

“It is emerging and diverse, and most of it is made up of small associations and has deficiencies in skills and human resources. It also suffers from several obstacles, such as the absence of mechanisms for controlling funding, especially from foreign agencies, in addition to weak public funding and the absence of its own tax system.”

The observer of associative life can record a number of observations, perhaps the most important of which are:

The end of the resurrection wave after three or four years.

A significant number of smaller organizations have not been able to impose their presence on the scene, and they are little active due to the lack of capabilities… They have a formal presence or have become completely absent.

The most prominent civil society organizations that, before the revolution, had a presence, effectiveness, radiance, and leadership in confronting the tyranny system, spreading the values of freedom and democracy, and contributing to the dissemination of an alternative culture, their activities shrank and lost their status and their luster faded to varying degrees, such as:

- The Tunisian League for the Defense of Human Rights,

- Tunisian Organization Against Torture,

- General Union of Tunisian Students,

- Democratic women,

- Tunisian Federation of Cine Clubs

- Tunisian Federation of Amateur Cinematographers,

- Free Writers Organization.

The civil society net recorded the emergence of a group of modern organizations that are distinguished by a clear vision, accuracy of programs with the availability of funds and human resources thanks to partnerships with international organizations and cooperation projects with international institutions or embassies such as:

- Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights,

- Al Bawsla,

The emergence of well-established international organizations that have opened branches in the country, such as:

- The World Organization Against Torture,

- International Center for Transitional Justice,

- Reporters Without Borders,

- Lawyers Without Borders,

There is an important group of organizations funded by Arab and Islamic countries and their affiliated institutions, such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the Emirates, and Turkey… They began to appear massively immediately after the revolution and played a decisive role in the elections for the Constituent Assembly on October 23, 2011, and the following. What distinguishes these associations:

- They are mostly charities.

- There is great ambiguity surrounding the ways and methods of financing these associations,

National public opinion followed with great astonishment the agreement of funds from a Gulf institution to a Tunisian “charitable” association, signed at the presidential palace and in the presence of the President of the Republic, Mr. Mohamed Moncef Marzouki.

There are many voices that consider that these associations are directly or indirectly involved in directing young people to hotbeds of tension (Syria in particular and then Libya) and terrorist groups active in Tunisia.

Political Participation

Before the Revolution, political life was under the control of one party and one man, where it is impossible to talk truly about the voluntary and broad participation of young people in political life in general and in decision-making positions in particular.

But after the revolution, the margin of freedoms imposed first by the people and subsequently approved and codified by the 2013 Constitution opened the way for a new political life based on freedoms, the rule of law and institutions.

Globalization affected people’s life choices, thus youth all over the world are being more reluctant to public life. Tunisia surprised the region with the 2008 protests in the Tunisian mining area and again in 2011 with the Jasmine revolution.

Youth played a major role in overthrowing the former regime, few weeks after the revolution, the debate about human rights, democracy and liberties became political and the older generation prioritized organizing elections rather than establishing a plan for the democratic transition.

The first elections left the Tunisian youth with disappointment, and this was witnessed during the next elections through a very limited youth participation in voting. Although, youth deserted polls, they started running for offices in national and most importantly local level such as municipal council seats.

During the 2019 elections, the candidate Kais Saied gathered the youth around him for an unexpected journey during his campaign. Youth create multiple online spaces to promote their candidate Kais Saied to replace the traditional media platforms. This was considered as a punishment from youth to the existing political sphere considered the cause of their disappointment.

The results of the presidential elections, in which a single candidate won the majority of the votes of the youth participating in the elections, compared to the rest of the candidates, raised a huge number of questions about the reasons for the youth’s support for Kais Saied, and the hopes they placed on him. What can be learnt from this experience for the benefit of youth participation in general? How does this experience help to understand the actual needs of young people that encourage them to participate in public life?

This reluctance is confirmed in the 2019 United Nations Development Program report entitled “Youth and Electoral Participation in Tunisia: Bilateral Turnout and Aversion.” The report stated that:

The reluctance seems to be explained before the 2011 revolution, given the nature of the political system in place at the time, which restricted political freedoms. However, the post-revolution period did not bring anything new. The percentage of youth participation in the Constituent Assembly elections did not exceed the ten percent threshold, which is a very weak number compared to the liberal spirit that the revolution added to political freedoms.

The participation of young people in the presidential elections was not limited to the support of Kais Saied in the electoral campaign but was also represented in his massive election by the general young electorate.

It is important to note that Kais Saied succeeded in attracting various youth groups, as it seems that he succeeded in presenting a discourse that fits their requirements. The image of an educated academic professor who speaks fluent Arabic and is capable of legal analysis par excellence, encouraged young people with higher degrees to elect him. They yearn for the rehabilitation of the intellectual in Tunisia and in public life, as they consider that the existing political class is controlled by uneducated people who do not believe in scientific production.

The young people who elected Kais Saied are young people who have suffered from the scourge of successive disappointments in light of the lack of consideration by the political class for their social and economic demands. In the sample study that we completed, which targeted 400 young men and women from Kais Saied voters in the first round, we find that 70 percent of Kais Saied voters are people who do not have a fixed income. It seems that this youth group considers social and economic benefits to be more important than other benefits, including those related to rights and freedoms.

Meanwhile, President Kais Saied emerged as a figure who was not known to have any suspicions of corruption. Rather, he is known for his abstinence from positions, clinging to fighting corruption, clinging to fighting nepotism, and determined to enforce the law on everyone, and he has always repeated: “The law must be like death that does not exclude nobody”. On several occasions, Kais Saied made fiery statements targeting the current political class, accusing them of involvement in corruption and “tampering with the Tunisians’ livelihood.” Thus, it can be concluded that the youth have searched for an honest candidate who is entrusted with the state, and who does not employ state agencies to serve his personal interests.

Religion

Follower of what is happening in the Arab world in general, and specifically, in Tunisia, would easily notice the presence of religion in the political life at a high proportion. This can be seen in daily life and in the results of elections in various representative entities.

Right after the Tunisian independence and the establishment of the new modern state, Habib Bourguiba, the Tunisian president, played the role of an “enlightened despot,” as Muhammad al-Sharafi described it. Bourguiba, while trying to modernize the new Tunisia, brought new interpretations of Islam according to his view of modernity.

It is also certain that most Tunisian political groups, have avoided engaging in an open clash with Islam and declare, from their various ideological positions, that religion is an essential part of the national identity. As Mr. Mahmoud bin Ramadan, a university professor of economics, a human rights activist and one of the leaders of the renewal movement said: “The cultural and political battle currently revolves around reading Islam, not abandoning it.” The communist workers party, declared in 1987 that Tunisians has no interest in the clashes between the Islamists and Bourguiba’s supporters.

The main reason leading to the involvement of young Tunisians in Salafist movements is social exclusion, the prevalence of uncertainty, the failure of the Tunisian schools, and the Salafi movement as a social elevator. The strategies of Salafi movements in attracting youth groups: the mobilization strategy, the strategy of recruitment in periods of political and security stability, and suddenly appearing on the scene in periods of tension and chaos, and the strategy of selection in dealing with religious texts by focusing on verses and hadiths promoting war and Jihad. Which serves its visions, so it appears to the young man that what the movement adopts is the core of religion and its essence, where the verses of jihad and fighting overcame its councils, and the strategy of persuasion, to end up showing the strategy of demolition and re-establishment, by deepening the rupture between the young man and his living reality in periods of crisis.

The social exclusion and the dire social conditions experienced by the Tunisian youth make them search for an alternative that provides them with symbolic icon that the state has failed to achieve, which raises their position in the social hierarchy. It includes unemployment, the fear from the future, the feelings of anxiety and tension they are experiencing, and the deprivation of the world of consumption. The Salafist movement did not arise out of a nothing. Rather, it is the result of important structural transformations and a historical pattern governed by the inefficient policies of a state that failed to implement a development model compatible with the requirements of the youth and compatible with their cultural specificities. It is the result of security policies such as the S17 listing. The high percentage of university youth who are involved in the Salafi movement is evidence that the educational institution is no longer the space that educates young people on moderation.

Since the revolution, there has been a growing interest from the Salafist movement in the political issues, which prompted it to contribute more to discussing political issues and to express an opinion on them. But perhaps what hindered the transformation of some factions of the jihadist Salafist current into political parties is the lack of a legitimate basis for partisan work and their lack of conviction in other Salafi views in this field. Therefore, the Salafi-jihadi current chose to operate within the unstructured public space because it would provide it with the required flexibility in managing its interests without entailing any legal, moral, or political obligations.

Therefore, there was a tendency within the Salafi-jihadi movement to make a great effort to communicate with its incubating social environment through its service, advocacy, and media projects.

Then came the turmoil that was reflected when we saw the successive clashes with the government around the US embassy on September 14, 2012, and then turned into open armed confrontations after the assassinations of Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi; This organization was accused of the two murders. The turmoil was also reflected in the periodic confrontations in Chaambi Mountains and in the border areas with Algeria.

Addressing violence within the extremist religious trends requires complex procedures between injunctive legal and communicative dialogue, filling voids, and spreading a positive religious culture. This also calls for distinguishing between what the state’s security, educational and development institutions can do, and what civil society structures must do in terms of communication, dialogue, rationalization, bridging gaps and developing their framing capabilities among young people, and their capabilities in attributing and supporting these efforts to encourage the integration of Salafi youth within the society.

Social acceptability

Social acceptability is an aspect of social behavior defined as the degree to which an individual is actively brought into social interactions by others, in individual and/or group relationships. Barriers to Social acceptability may be prejudice, stigma.

Right after the independence, the Tunisian constitution and the establishment of a Tunisian independent political system united the nation around one unique Tunisian identity that, in some sorts obliterate the diversity of cultures, community characteristics and cultural tribalism dated back to the installments of north African tribes in the region.

The historical background of Tribal conflicts and traditional social structure and the hostile traditions between the countryside and the city in Tunisia led to a strong social stigma that is associated with historical interpretations and deep-rooted social behavior.

Sociologist Erving Goffman draws on autobiographies and case studies to analyze a stigmatized person’s feelings about himself and his relationships with ordinary people. Goffman focuses on the fact that stigma is not a fixed and inherent attribute of a person, but an experience of meaning and difference. It sheds light on how stigmatized people deal with their depraved identity, which means that stigmatization disqualifies them from full social acceptance by an audience that is “normal.”.

[1]

A social stigma is the extreme disapproval of a person because of social characteristics that separate them from other members of society. It is the deviation or disapproval of a person because it does not fit into the necessary social norms of a particular society. A social stigma can be so profound that it can overwhelm positive social feedback about how the same individual adheres to other social norms.

The degree to which an individual is actively drawn into social interactions by others, in individual and/or group relationships, is referred to as social acceptability. Prejudice and stigma can be barriers to social acceptability. Children, teens, and adults are all affected by social acceptability.

Peer pressure causes children and teens to undertake a variety of activities in order to be accepted by their peers. Peer pressure can influence how they style their hair and what clothes they wear. It also influences what people are prepared to do to be accepted by others whose companionship they value, such as smoking, drinking, cursing, and much more.

Violent extremism in Tunisia

Violent extremism pre-revolution in Tunisia

The Revolutionaries during the 70s:

The underlying foundations of Sunni Salafi-jihadi movements return to the last part of the 1970s. It started explicitly in Egypt, when jihadist groups were shaped for the purpose of overthrowing the political systems in the Arab world. A well-known booklet named “The Absent Obligation” filled in as a guide for these developments.

Its Egyptian creator, Muhammad Abd al-Salam Farag, says in his leaflet that Muslims “hold fast to numerous strict commitments, however they have missed a fundamental commitment, which is jihad.” Faraj required the need of battling the “close to adversary” – which means the decision systems in countries with Muslim majority over battling outer foes, or the “far off foe.”

The jihadists of that time addressed an overthrow style as opposed to an all-encompassing development. They assassinated the Egyptian President Mohamed Anwar Sadat in 1981.

The Afghan Project, 80s:

At the point when Egypt’s jihadists, after the death of Sadat, started to escape the country due to the security crackdown against them, Afghanistan was the most secure asylum, which started to become a “jihadist field.” The United States and the Arab Gulf states supported the movement of Muslim young people to battle against the Soviet Union and the socialist government in Kabul.

Al Qaida, 90s:

The evolution of al-Qaeda was different from what Azzam wanted, who was killed in a car bomb in 1989. No one has yet claimed responsibility for his assassination.

And the idea of global jihad began to form a major heading of Al Qaeda’s activity. After the victory over the Soviet forces in Afghanistan, the jihadists began to return to their homelands.

Some tried to transfer “victory over a superpower” to their countries, so tourism was targeted in Egypt, Libya also witnessed confrontations, and the bombings reached Saudi Arabia, and many cells were seized in Jordan.

Algeria has witnessed a decade of bloody violence, although the reason is related to preventing the Islamists from assuming power after they won the elections in the country in the early 1990s. However, the returnees from Afghanistan – who did not participate in the elections in the first place – had started to form armed groups from the start.

Others who returned from Afghanistan wanted to repeat the experience elsewhere, so they took part in the fighting in Bosnia, Tajikistan, and Chechnya.

The jihadist-coup ideas coming from Egypt were mated with the Salafi ideas coming from the Gulf states and Afghanistan. The new outcome was Salafi jihadism.

This was later translated by an alliance between the Egyptian, the current leader of al-Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and his former leader, the Saudi millionaire who supported and funded the Afghan jihad, Osama Bin Laden.

In 1998, he announced the establishment of the International Islamic Front for Fighting the Jews and the Crusaders. The so-called “global jihad” of al-Qaeda began. In the same year, jihadists bombed the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Three years later, the jihadists bombed the American destroyer Cole on the coast of Yemen.

9.11, the 00s:

On the morning of the eleventh of September, four civilian aircraft, piloted by jihadists, attacked major buildings in New York and Washington, DC, in the United States of America.

The attack killed about three thousand people. And led to the war in Afghanistan, and the prosecution of suspects. Al-Qaeda jihadists began with a new method by recruiting and training young men and sending them to their countries to carry out bombings, as happened in Bali-Indonesia (2002), Casablanca (2003), Madrid (2004), and London and Amman (2005).

Saudi Arabia also witnessed confrontations with jihadists between 2003-2007. But the US occupation of Iraq in 2003 played a major role in the emergence of a new generation of militants led by the Jordanian, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Al Qaeda in Iraq, or Mesopotamia, provided a more radical model of “jihadist” movements.

Recordings of massacres spread online, as did suicide attacks and kidnappings. Al-Zarqawi was killed in a US air strike in 2006.

Since 2008, al-Qaeda began forging new alliances, and the organization’s branches spread in more than one place. In Iraq, Al Qaeda became known as the “Islamic State in Iraq.”

In Yemen, the country’s jihadists have united with their Saudi counterparts under the umbrella of “Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula”.

In Algeria, its jihadists pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda, under the name of “Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb,” and expanded their activities to the Sahel countries, south of the Sahara.

Also, the Somali “al-Shabab al-Mujahideen” movement joined al-Qaeda later, after the organization’s leader, Osama bin Laden, was killed in a special American operation in 2011.

The Arab Spring:

The killing of Bin Laden posed a challenge to Al Qaeda and the jihadist movements, but the biggest challenge was the Arab Spring.

The protest movements in the Arab world, which overthrew powerful regimes in the region such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen, marginalized the jihadist ideology.

However, the escalation of violence in more than one place in the Arab world, especially in Syria, restored the impetus to these movements. Syria turned into a magnet for jihadists from all over the world, and armed jihadist movements multiplied.

Differences emerged between these movements, especially between the Al-Nusra Front, which is linked to Al Qaeda, and the “Islamic State” organization, which controlled a large area between Iraq and Syria.

This organization, which has changed its name several times, and it roots back to Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia, occupied Mosul in June 2014.

This expansion, the declaration of a caliphate in the areas controlled by the organization, and pictures of the beheadings of journalists, prompted the announcement of air strikes on it by the United States of America and allied countries.

When talking about Violent Extremism in Tunisia, we mainly talk about jihadist Salafi groups. Since the 80s, the strategy of this group, mainly focused on the establishment of “Khilafa” and got its inspiration from the well-known book, used as reference, Management of Savagery or Administration of Savagery.

In his book, Abu Baker Naji, targeted to provide a manual or guide for Al Qaeda and other extremist groups on how to establish an Islamic Caliphate. The book was published online in 2004 and was shared massively among extremist groups.

The first armed operations directed against the Tunisian state to destabilize it date back to the eighties of the last century. This comes after the emergence of several jihadist factions in Egypt in the late 1970s calling for the overthrow of existing regimes in Arab countries in favor of “theocratic” regimes. This upsurge in the jihadi factions coincided with the emergence of the book “The Absent Obligations” by its author, Muhammad Abd al-Salam Faraj, in which he blames Muslims for abandoning a basic obligation of their religion, which is jihad and invites them to start fighting the near enemy, which are the regimes in Muslim-majority countries before devoting themselves to fighting the distant enemy from non-Muslims.

The Islamic trend movement in Tunisia (the current Ennahda Movement) was one of the movements that was inspired by this thought to adopt the thesis of “armed radical change and revolutionary coup” and challenge the existing regime with various operations that affected the headquarters of the ruling party and some of its political symbols to the point of organizing a coup after the security and military institutions were penetrated in the year 1987.

In October of the same year, a group calling itself “Islamic Jihad” launched an attack on a post office and a police station and claimed responsibility for the bombings that hit two hotels in Sousse and Monastir. As a result of these events, the regime arrested the leaders of this organization, headed by the former member of the Islamic trend, Habib al-Dhawi, and the group’s mufti, Muhammad al-Azraq, was executed after he was handed over from Saudi Arabia, where he sought refuge.

The eighties came to an end with the emergence of an organization that called itself “Precursors of Redemption” led by the former member of the Islamic Trend Movement, Habib Lassoued, who was likely to have been eliminated in a security campaign in the early 1990s.

During the eighties, the groups were persecuted in Tunisia and the government led several operations arresting leaders and supporters. This led the fanatics to flee the country and join the war in Afghanistan where several fatwas for jihad were issued, perhaps the most important of which is the fatwa of the Jordanian-Palestinian Sheikh Abdullah Azzam, which states that jihad is an “Individual Obligation – fardh ain” on any Muslim, if any Muslim lands are occupied.

In fulfillment of these fatwas and to escape from the oppression of the regime, a number of young men and leaders pursued inside Tunisia went to Afghanistan, some of them belong to the Islamic trend movement and others to the Tunisian Islamic Front with a Salafist ideology, most of its members and founders joined Peshawar, Pakistan (the crossing point to Afghanistan), perhaps the most prominent of them is Muhammad Ali Harrath and Abdullah Al-Hajji, who was imprisoned in Guantánamo Bay after the overthrow of the Taliban.

Tunisia was among the countries targeted by terrorist attacks on two occasions to destabilize the regime and hit the national economy by targeting tourism. The attack on the synagogue in Djerba in 2002, which left 19 dead and 30 wounded, most of them foreign tourists. The attack was carried out by a Tunisian jihadist named Nizar Nawar, who had been training at an al-Qaeda camp in the Pakistani city of Karachi and the events of Sliman in 2007 that took place between the Tunisian security forces and the “Soldiers of Assad Bin Al Furat” battalion led by Al-Assad Sassi, who fought in both Bosnia and Afghanistan. These events claimed the lives of 15 militants and subsequently arrested hundreds of those accused of belonging to the Salafi jihadist ideology.

Post-revolution, the rise of Violent extremism.

As the only country in the MENA region to have quite successfully taken a democratic path, Tunisia holds much promise. Notwithstanding continuous political and economic challenges, Tunisia succeeded in holding several free and transparent elections and ratified a constitution in 2014 seen by many observers as the most advanced legal text in the region. However, the country still faces a number of challenges most notably violent extremism. Since the eruption of the Arab Spring in 2011, Tunisia has been struggling with a high number of terrorist attacks. On the 18th of March 2015, three gunmen attacked a group of tourists at the Bardo National Museum in the capital Tunis. Three months later, a lone gunman attacked a group of British tourists at a beach resort in the city of Sousse. On the 24th of November 2016, a dozen presidential guards were killed on a bus by a suicide bomber in downtown Tunis. All of these deadly attacks were followed by sporadic terrorist attacks especially in the south, near the borders with Libya. In addition, a significant number of foreign fighters joining the Islamic State in Syria, Libya and Iraq were Tunisians. (Watanabe, 2018). According to the data released by The Soufan Group in 2015, Tunisians constituted the single largest group of foreign fighters in Libya and Syria, with around 6000 fighters (Soufan Group, 2015). A number of these fighters have already returned home, some of whom are not even known to the authorities (Watanabe, 2018).

The convergent trends of increasing violent extremism and reinforcing democratization since the fall of Zine al- Abidine Ben Ali is quite a puzzle. Existing scholarship suggests that we should expect to see violent extremism declining while the country moves forward to more consolidated democracy (Macdonald and Waggoner, 2018; Krueger, 2007). Alan Krueger argues that extremists and terrorists emerge from countries where political and civil liberties are limited (Krueger, 2007: p 74). Puddington brings to light that 90% of terrorist attacks in 2013 took place in either “not free” or “partly free” countries (Puddington, 2015). However, the Tunisian case is quite different. Although Tunisia is classified as a free country by the Freedom House, the number of Tunisians joining radical groups either in Tunisia or foreign groups raises concerns. This background note will address this issue and attempts to answer a few questions: What are the violent extremist groups that Tunisians have already joined, in Tunisia and abroad? What are the root causes of violent extremism? What kind of strategies have the Tunisian government adopted to counter violent extremism?

Extremist groups in Tunisia

Existing data shows that there are a number of violent extremist groups operating in Tunisia. In addition to the task of planning and executing terror attacks, these groups also work on recruiting Tunisians for foreign conflicts, more particularly in Libya, Syria, and Iraq. Among these groups, ISIS has the most powerful ability to recruit Tunisians for its local and international operations. This is done thanks to ISIS large network, as it cooperates with local groups operating in Tunisia, including Ansar al- Sharia, Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade and Mujahidin of Kairouan.

Ansar al- Sharia

Ansar al- Sharia (AST) is a violent Islamist group that works to implement Sharia Islamic law as the country’s prime source of laws. In order to achieve this, Ansar al- Sharia has recourse to proselytizing through religious education and the provision of social services. In order to increase its platform for more violent jihad, the AST sought to enforce strict laws, largely based on the duty to command moral acts, and looks forward to carrying out more jihad by executing violent terror attacks. According to a number of reports, leaders of the AST pledged their allegiance to ISIS in 2014. Since then, the AST has become the largest ISIS affiliate in Tunisia. The number of Tunisians joining ISIS in Libya and Syria was so high that AST lamented that the conflicts in the Middle East have “emptied Tunisia of its young generations”. ISIS propaganda has remarkably relied on Tunisians who participated in a significant number of ISIS’ terror attacks.

According to some reports, it seems that the cooperation between AST and ISIS started in 2014, when AST deputy “Emir” Kamel Zarrouk joined ISIS in Syria (Long War Journal, 2014). Since then, a strong relationship between ISIS and AST has been established. In 2015, ISIS released a video in which a Tunisian militant, known as Abu Yahia al-Tounessi threatened all Tunisians of war and blood, unless they join ISIS and claim allegiance to its leader Abu Bakr al- Baghdadi (Reuters, 2015). ISIS also released another video in 2015, in which a group of militants called “Tripoli Province” threatened the Tunisian government of further attacks (Counter Extremism Project, 2015). It would be remiss not to mention that AST had previously cooperated with al- Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, along with other extremist groups including the Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq. In 2014, the leader of the AST, Abu Iyad al-Tounessi released a statement to call for unity between all the jihadi groups and set aside any potential ideological disagreements (Long War Journal, 2014).

Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade

Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade is a militant group that claimed responsibility for a large number of attacks against the Tunisian army and security forces. It pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2014. Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade is known to the Tunisian authorities as experienced fighters of the Islamist rebellion in northern Mali as well as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Since the fall of Ben Al’s regime, Okba Ibn Nafaa has been continuously attacking the Tunisian army and other security forces, especially in the checkpoints near the Libyan and Algerian borders. Several attacks were conducted by Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade, including the 2015 attack on Tunisia’s Hotel Imperial Marhaba that ended up with around 37 casualties, and the 2014 attack on the Tunisian military forces near the Algerian borders. In September 2014, the Tunisian authorities disclosed Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade’s plan to attack the parliament during the 2014 parliamentary elections. The group’s leader, known as Lokmane Abou Sakhr, was killed by the Tunisian forces in 2015, after being accused of the attack on Bardo Museum that killed around 21 people including tourists and security forces.

Mujahidin of Kairouan

Mujahidin of Kairouan is a violent extremist group that pledged allegiance to ISIS in May 2015. The group was identified by the authorities when ISIS English magazine Dabiq released an issue on the activities of the group in Tunisia, along with a picture of Kairouan mosque on the cover (Al- Arabia, 2015; Tunisia Live, 2015).

Tunisian Combat Group

The Tunisian Combat Group is classified as a foreign terrorist organization by the US Department of State. The group was founded by Abu Iyad al- Tunisi and other commanders in al-Qaeda in 2000. This group was primarily founded as a bridge to unite Tunisians coming back home from Afghanistan to work against the Tunisian government. Since its establishment, the Tunisian Combat Group claimed responsibility for a number of violent attacks. For instance, the TCG provided foreign passports to al-Qaeda combatants who killed anti-Taliban leader Ahmad Shah Massoud in September 2001 (New York Times, 2001). In April 2001, militants from both the TCG and al-Qaeda were arrests in Rome for planning an attack against the US embassy. This incident impelled many embassies and consulates across Europe to close their doors for two days as a precaution against any potential terrorist attack.

Ansar al-Dine.

Ansar al-Dine is an affiliated group with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. It operates mainly in Northern Mali and Southern Algeria. According to the latest data, Tunisians make almost 600 combatants among the group’s members.

Joining extremist Groups in conflict zones.

Recruitment Strategies

In order to recruit new members, operatives or supporters, violent extremist groups use a number of tools and techniques. While some recruitment tools are quite costless, others require substantial funding and investment, including the use of a network of other groups or individuals or the maintenance of some infrastructure. In the Tunisian context, and according to the authorities’ reports, recruitment often takes place in religious institutions such as the mosques. Recruitment may also occur online or through particular social contacts as these techniques provide an easy and costless access to lower socioeconomic areas and even to prisons. Recruitment in Tunisia may also occur in areas where violent extremist groups already enjoy some territorial control, such as the Tunisian-Algerian borders.

Direct Recruitment

Direct recruitment occurs when a direct personal contact between the recruiter and the individual takes place. Through direct recruitment, recruiters generally select particular geographical areas where it is quite easy to find sympathizers or supporters of a particular violent group. The selection of these new members is not random. It is made according to the group’s needs, ranging from militants to professionals such as doctors and engineers. Active recruitment requires substantive funding. The extremist violent group assigns one or a number of individuals to select and recruit new members. In order to effectively fulfil such a task, these individuals need a source of funding to sustain their living expenses and provide the necessary environment for the recruitment. This ranges from setting up meeting places, providing fake documents, booking flights tickets and training. All these expenses and others are generally met by the recruiter. Other forms of funding may come from donations from followers and sympathizers of the extremist group.

Indirect Recruitment

Indirect recruitment takes place when new individuals are recruited through indirect means, such as media campaigns and online communication tools. The use of social media as a tool to recruit new members in the extremist violent groups is common in Tunisia. According to the authorities’ reports, these groups heavily rely on social media channels and internet to introduce their ideology, disseminate their propaganda and work on new recruitments. This strategy allows these groups to spread their ideas at a low cost and identify potential new members who are psychologically and even financially ready to join these groups.

While social media channels are the easiest and the largest windows for indirect recruitment of new individuals, violent extremist groups in Tunisia have largely used traditional strategies including printing leaflets, holding meetings and broadcasting programs targeting young people who are willing to join these groups. One good example of this is the ISIS-monthly magazine, Dabiq, available since 2014 and inspired by Al-Qaeda’s magazines. In Tunisia, recruitment using traditional strategies was quite easy especially in 2012 and 2013. Violent extremist groups had an easy access to young Tunisians through leaflets and public meetings. However, since 2014, traditional recruitment has gradually become more complex as tightened security measures have significantly increased. Accordingly, indirect recruitment was limited to online communication tools.

Although access to the internet, including the creation of websites and the use of social media channels such as Facebook and YouTube, is almost free, violent extremist groups, especially ISIS, create high-quality content as it employs a number of media experts and high-tech equipment. In view of the quality of the content and the frequency of distribution, these violent groups use a large number of moderators and bloggers who are experts in the field.

Fighting as a violent extremist.

Tunisians have an extensive history participating in violent extremist groups abroad and within Tunisia. In Afghanistan in the 1980s they played a small role, contributing only about 400 mujahideen. Likewise, during the Iraq War they constituted only about 5% of foreign fighters in al-Qaida in Iraq. However, in this time they built substantial linkages between violent extremist groups and local recruiters and financiers that facilitated a large exodus after the 2011 revolution.

[1]

The Tunisians Tarek Maaroufi and Seifallah Ben Hassine founded the Tunisian Combatant Group in 2000 to send Tunisians overseas to Chechnya, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Europe, and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Imprisoned in 2003, Ben Hassine was released after the fall of Ben Ali and founded Ansar al-Sharia.

[2] Ansar al-Sharia started heavily recruiting a move that was tolerated at the time by the ruling Ennahda government despite their public intellectual and political spats. Tunisians flocked to Syria, many at first to join opposition groups but later joining al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State. Likewise, due to proximity and historical connections a large number joined the Islamic State in Libya. Traveling to Syria and Libya was easily facilitated due to a lack of airport controls in Tunis and visas in Libya and Turkey (the main entryway to Syria).

Within Tunisia, by 2013 Ennahda had cracked down on Ansar al-Sharia and in return they openly denounced the Tunisian government and its leaders. In 2012 they were behind an attack on the U.S. Embassy after a film that debased the Prophet Mohammed. As the flow of Tunisians to foreign violent extremist groups slowed, local violent extremist groups began waging a protracted insurgency against the Tunisian state. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb established itself on the Algerian border in Kasserine and renamed itself Katiba Oqba ibn Nafa’a (KUIN). Since it mainly targets police and security forces, it is an insurgency rather than a country-wide terrorist campaign. In 2014, part of KUIN splintered off and joined the Islamic State, renaming itself Jund al-Khilafah Tunisia. With less concern for civilian casualties, violence increased both in regions along the Algerian border and in more heavily populated areas

[3]. In 2015, they orchestrated three major terrorist attacks in 2015 in the Bardo Museum, Sousse beach, and a Presidential Guard bus. In 2016, the Islamic State in Libya even launched an attack across the border on Ben Guerdane and captured the city, though they were quickly pushed out

[4]. While the Tunisian security forces have stepped up their raids and coordination abilities, both Jund al-Khilafah Tunisia and KUIN have about 175 to 185 fighters. Additionally, a number travel through the Libyan border, suggesting returning fighters will be a boost to their operations. Though a small force, KUIN is more closely associated with al-Qaeda’s operations across North Africa, particularly in Algeria. It has been easily able to replace lost fighters and work with local populations for basic needs, though it does not have a wide base of support. It is exactly this insurgency’s continued infiltration that makes addressing the root causes of radicalization so important.

Root Causes of Youth Radicalization

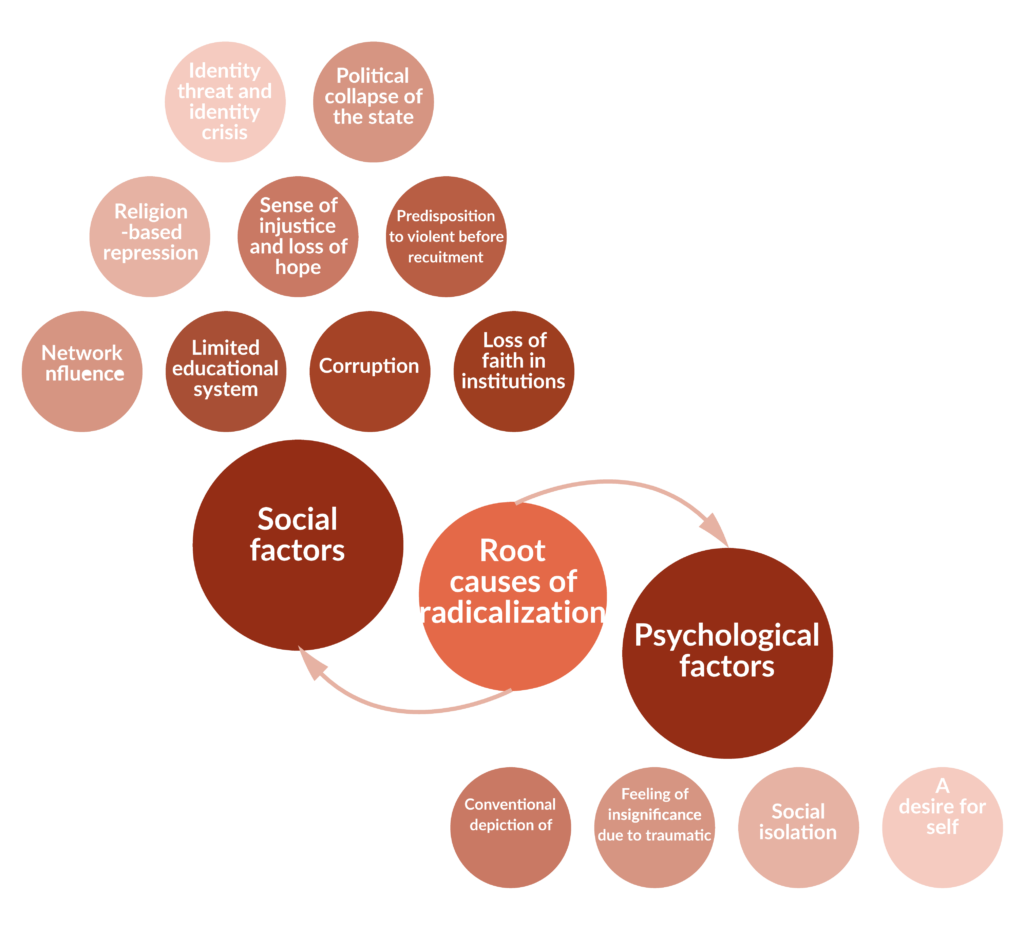

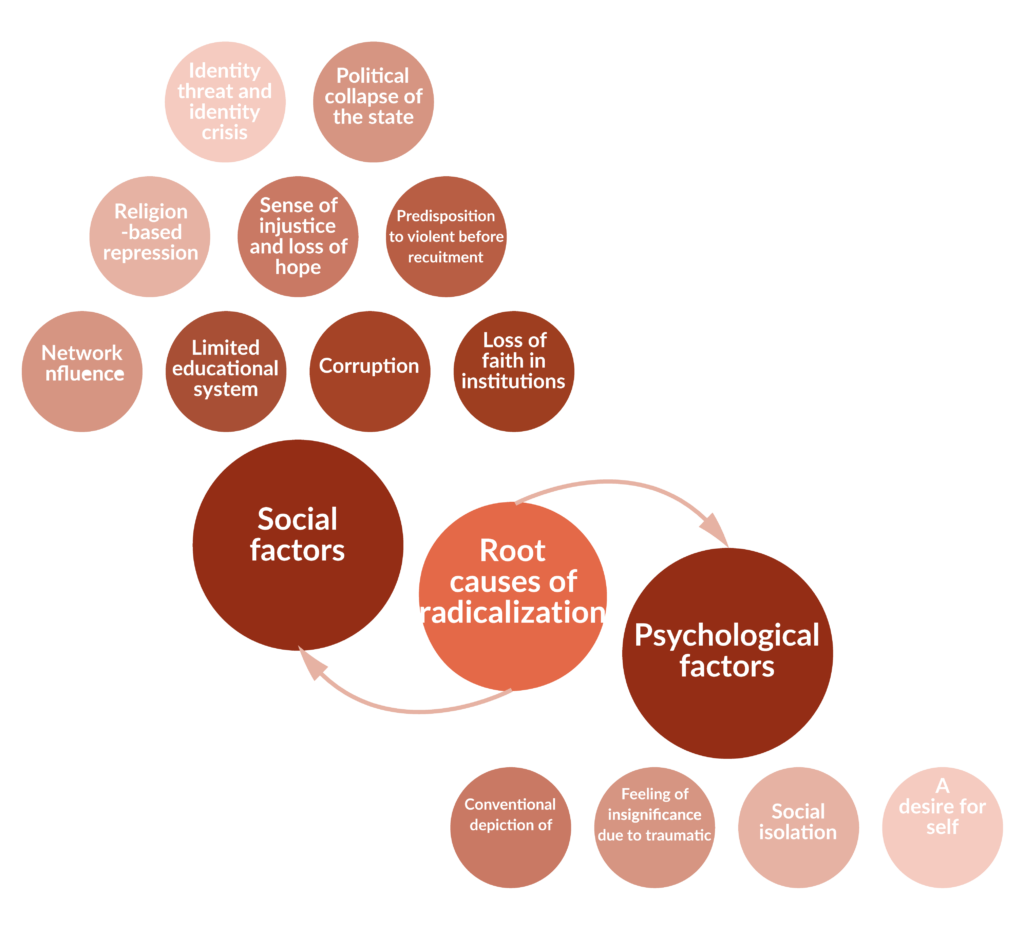

Motivations to support and/or join violent extremist groups are divided into 2 categories: psychological and Societal drivers.

Psychological drivers such as the feeling of insignificance due to traumatic experiences, social isolation, Conventional depictions of masculinity and femininity, the desire for self-destruction represents factors that influence individual personal process of radicalization. These drivers deepen the frailty of someone’s personality and create a void that can be easily filled by extremist ideas and beliefs.

As an important psychological driver, feeling of insignificance due to traumatic experiences, and by traumatic we mean experiences such as emotional displacement (losing love or a key romantic relationship) as well as sexual abuse which can lead a person to make decisions in a temporary emotional state that may support violent action, or as Niconchuk terms it, “heroic limbo.” Acts of violence are by consequence, in this context, a way for individuals to overcome their trauma-inflicted feelings of insignificance. These feelings are countered by a strong desire for glory and significance where one seeks to become greater than one is.

On the other hand, societal drivers derive more from a society common history and a cumulation of tensions experienced by the community. These drivers can be summarized in Identity threats and identity crisis, a predisposition to violence before recruitment, network influence, loss of faith in and active abuse by existing structures of justice, corruption, political collapse of the State, sense of injustice and loss of hope, Religion-based discrimination and repression by the State, a limited educational system.

In Tunisia and according to the study subjects of MEF research, the most significant driver is sense of injustice and loss of hope which is defined as the contrast between the high expectations of people after the Arab spring meeting unresponsive state institutions which drives individuals to feel marginalized and powerless. They lose hope and become convinced that problems in Tunisia are hopeless and that they would never improve with unemployment, indifference, and an increasing low self-esteem still existent.

The mind map bellow explains to a certain extent, that the root causes of radicalization are mainly personal and complex. No algorithm or a pattern exists in studying the vulnerability of youth to radicalization.

Figure 4 Root causes of radicalization

[1]

Figure 4 Root causes of radicalization

[1] Haim Malka and Margo Balboni. “Tunisian Fighters: In History and Today.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2016.

[2] Malka and Balboni.

op. cit.

[3] Matt Herbert. “The Insurgency in Tunisia’s Western Borderlands.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. June 28, 2018.

[4] “How the Islamic State Rose, Fell, and Could Rise Again in the Maghreb.” International Crisis Group. Middle East and North Africa Report N

o178, 24 July 2017.

[1] Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Figure 4 Root causes of radicalization

[1] Haim Malka and Margo Balboni. “Tunisian Fighters: In History and Today.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2016.

[2] Malka and Balboni. op. cit.

[3] Matt Herbert. “The Insurgency in Tunisia’s Western Borderlands.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. June 28, 2018.

[4] “How the Islamic State Rose, Fell, and Could Rise Again in the Maghreb.” International Crisis Group. Middle East and North Africa Report No178, 24 July 2017.

[1] Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Figure 4 Root causes of radicalization

[1] Haim Malka and Margo Balboni. “Tunisian Fighters: In History and Today.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 2016.

[2] Malka and Balboni. op. cit.

[3] Matt Herbert. “The Insurgency in Tunisia’s Western Borderlands.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. June 28, 2018.

[4] “How the Islamic State Rose, Fell, and Could Rise Again in the Maghreb.” International Crisis Group. Middle East and North Africa Report No178, 24 July 2017.

[1] Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.