Methodology

Table of Contents

To answer the problematics of the study, we apply a qualitative multimethod research approach for data collection. Although the terms “multimethod” and “mixed method” are often confused or used interchangeably in the related literature, nevertheless, it is possible to draw a sharp distinction between both terms. According to Tashakkori and Teddlie (2003, p 11), multiple method research could be defined as “research in which more than one method or more than one world-view is used”. From this broad definition, they derive three core categories of multiple method research: (a) multimethod research, (b) mixed method research, and (c) mixed model research.

However, mixed method and mixed model research are regrouped under the term mixed methods, as they both comprise either a simultaneous or sequential use of both quantitative and qualitative data collection procedures and techniques. In contrast, multimethod research consists of using two different methods (e.g., Ethnography, Case study, etc..) or data collection procedures from the same methodological tradition (Qualitative or Quantitative.).

The adoption of a qualitative multimethod research approach ensures that our research questions are not explored through one lens, but rather a variety of lenses which allows for multiple facets of the phenomenon to be revealed and understood. Furthermore, it is consistent with the inductive theoretical drive inherent to our study, conducted on a discovery working mode due to multiple reasons and constraints, such as:

- The complexity of research questions.

- Scarcity of research literature on youth radicalization in Tunisia.

- The absence of a single overarching guiding theory on youth radicalization.

Research Design:

Multiple case-studies:

From a broad array of designs to qualitative research, we select to module our study on a multiple case-studies design. Case study method enables a researcher to closely examine the data within a specific context. In most cases, a case study method selects a small geographical area or a very limited number of individuals as the subjects of study. Case studies, in their true essence, investigate and explore contemporary real-life phenomenon through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions, and their relationships. Yin (1983:23) defines the case study research method “as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used”.

According to Yin (2003), a case study design is considered appropriate when: (a) the focus of the study is to answer “how” and “why” questions; (b) you want to cover contextual conditions because you believe they are relevant to the phenomenon under study; or (c) the boundaries are not clear between the phenomenon and context. Following these considerations, the case study design is considered appropriate for our study given that: (a) the focus of the study is to discover root causes and routes of youth radicalization in Tunisia; (b) measuring the influence of multiple exclusion dynamics on youth radicalization in Tunisia; (c) youth radicalization in Tunisia is considered as a phenomenon specific to urban-peripheral contexts.

On the other hand, multiple case-studies are included to enhance the explanatory power and generalizability of the data collection and interpretation process. It will enable a replication of findings and an exploration of differences between and within cases. Based on comparisons, the boundaries between the phenomenon and micro-contexts will be assigned, macro-dynamics will be recognized, and the influence of each specific inclusion variable will be defined.

All research is based on some underlying philosophical assumptions about what constitutes valid research and which research methods are appropriate for the construction of knowledge in each study. Therefore, a proper conduction and evaluation of any research requires a clarification of these assumptions.

Following Stake (1995) and Yin (2003), we will base our approach to case study on a constructivist paradigm. Constructivists claim that truth is relative and that it is dependent on one’s perspective, social trajectory, and positionality in each socio-historical conjecture. This paradigm “recognizes the importance of the subjective human creation of meaning but doesn’t reject outright some notion of objectivity. Pluralism, not relativism, is stressed with focus on the circular dynamic tension of subject and object” (Miller & Crabtree, 1999, p. 10). Constructivism is built upon the premise of a social construction of reality (Searle, 1995).

The rationale for basing our approach to the case study on this paradigm is grounded in the recognition of a necessary close collaboration between the researcher and the participant, enabling participants to elaborate on their perceptions in interactive settings, and to construct their trajectories in a narrative form (Crabtree & Miller, 1999). Through these interactions and narrations, the participants can describe their views and experiences, which enables the researcher to grasp a thick description of the participants’ actions, motivations, and perceptions of reality.

Research Methodology

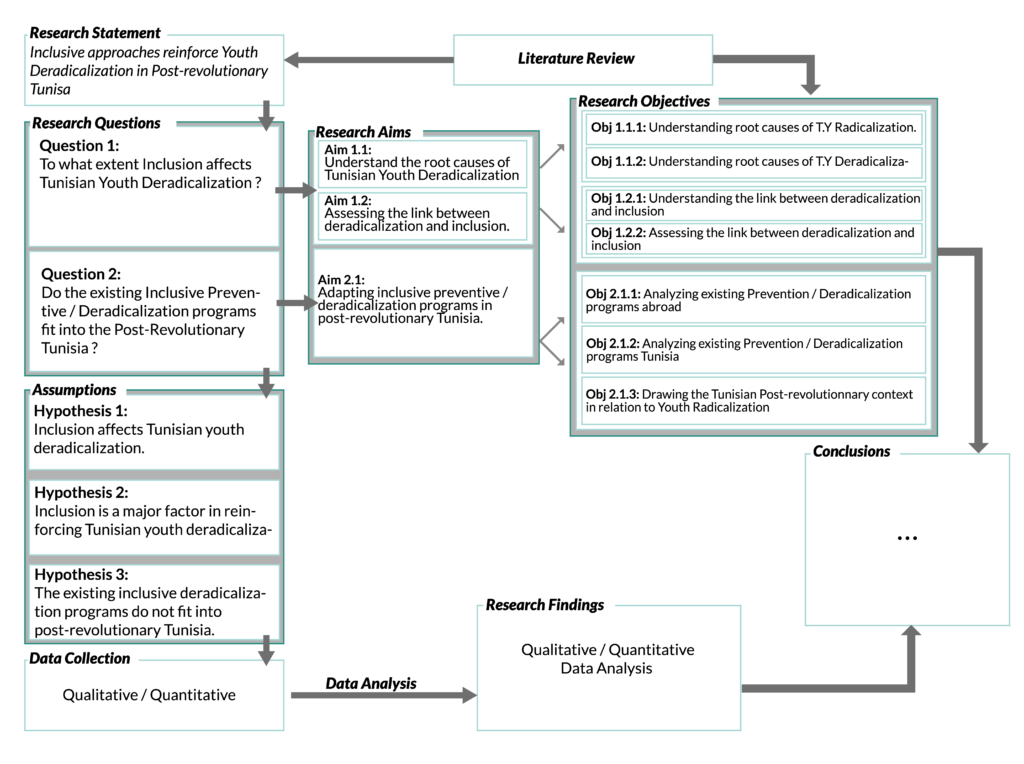

The research methodology is based on a mix method approach (qualitative and quantitative analysis) to answer the research questions, reach its objectives, and develop a comprehensive understanding of the role of inclusion perception in the radicalization and deradicalization phenomena.

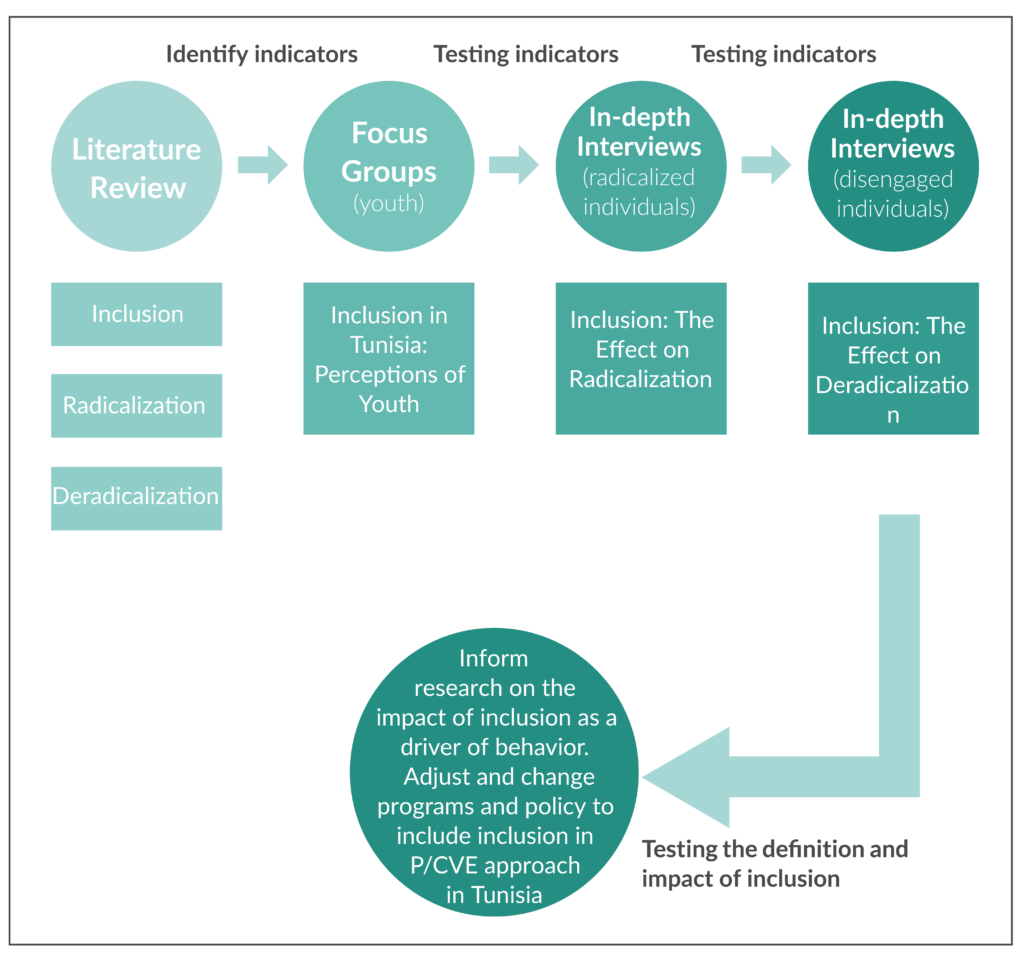

Research question

Based on three assumptions, the research statement asserts that inclusive approaches reinforce Youth Deradicalization in Post-revolutionary Tunisia. The study answers two research questions:

- To what extent Inclusion affects Tunisian Youth Deradicalization?

- Do the existing Inclusive Deradicalization programs fit into the Post-Revolutionary Tunisia?

Methodological path:

The research aims to follow the changes of the perception of inclusion throughout the process of radicalization and disengagement. The change of the perceptions is believed to assert the importance of inclusion and more specifically the importance of certain inclusion indicators in the preventing violent extremism and deradicalization.

Data Collection:

To put the research into its context, data was collected in the years of 2018 and 2019 meaning the research is based on data, information and analysis undertaken from 2018 to the beginning of 2020. However, the research team consider that the research outputs are still valid since no considerable developments or changes were made in the field of preventing violent extremism and deradicalization programing in Tunisia and the Maghreb Region.

The data is collected through reaching out to Tunisian youth, radicalized individuals, returnees, and local and national stakeholders. During the data collection process, the research team abide by the study’s ethics and security protocols.

The language used during the data collection is the “Tunisian Dialect”. The choice of language would be for the sake of preserving the data content. Moreover, it would help create a better understanding of the post-revolutionary Tunisian Context.

As stated, the research overlay the process of deradicalization and the change of inclusion perception among Tunisian youth. In this study we focus on portraying three perceptions of inclusion among 3 different groups of research population.

The research data is collected through 3 phases using different data collection tools according to the methodological path and framework.

First Phase: Literature Review

The purpose of a literature review is to establish the importance of the topic at hand and to provide a background information about it. Furthermore, it allows the researchers to effectively place themselves in a scholarly conversation.

With the data collected, the research team aims at creating a comprehensive paper that works with books, academic and journalistic articles, research papers, policy briefs and accessible governmental data to establish a primary understanding of the topic.

In addition, the purpose of the literature review is to depicts the Tunisian context through understanding the background of each indicator of the inclusion definition. The data comprises historical, societal, and anthropological facets.

The literature review covers:

- Defining Radicalization.

- Root causes of supporting Violent Extremism Groups.

- Root causes of joining Violent Extremism Groups.

- Defining Deradicalization.

- Root causes of Deradicalization / Disengagement.

- Defining Inclusion.

- Understanding the Tunisian context

- Understanding the link between Prevention / Deradicalization and Inclusion.

- Deradicalization and prevention programs in Tunisia.

- Deradicalization and prevention programs abroad.

The literate review concludes the baseline definition of inclusion based on international and national interpretations while describing the process of radicalization and deradicalization.

Second phase: Focus groups

In order to define and contextualize the perception of inclusion in Tunisia post revolution, primary data from focus groups with youth from the targeted population intend to test the literature review-based definition of inclusion.

Population:

Kasserine: Ezzouhour neighborhood

Kasserine, a small town in midwestern Tunisia, is also spelled Al-Qaṣrayn (Al-Qaṣrayn). The town is an important market, road and railway hub, and the center of an irrigated agricultural area.

Kasserine’s economic activities are based on the cultivation of olives and esparto grass and the manufacture of paper pulp. It is also known for the nearby Chaambi National Park, home of the country’s endangered mountain and a hideout for several extremist groups.

Kasserine is a one of the first Tunisian regions where the uprising of 2011 started. The protests in 2011 were a result of decades of marginalization and socioeconomic exclusion.

The research is conducted in the neighborhood of Ezzouhour in the city center of Kasserine, with a population of 21 819 individuals and a high unemployment rate of 32.45 compared to 14.82 at national level and an illiteracy rate of 28.39 which is considered significant in comparison with a national illiteracy rate of 19.27.

Tataouine: Ghomrassen

The Tataouine Governorate is Tunisia’s southernmost governorate, and the only one that shares borders with both Algeria and Libya. It is also the biggest, with a total area of 38,889 km2. It was virtually tied for second least populated with a population of 149453.

The governorate of Tataouine is home to Tunisia’s greatest natural resource fields, including Borma, Adem, Chourouk, and Nawara, which will shortly begin gas production and is believed to be the country’s largest gas field. Despite its wealth of natural resources, the governorate has poor development indicators: unemployment is over 32 percent, about double the national average of 15 percent, and the governorate’s economy is stagnant.

One of the cities of Tataouine, Ghomrassen is the third most populated city with a population of 15957 and a high unemployment rate of 21.05 in comparison with a national rate of 14.82. 20.28 % of females in Ghomrassen are illiterate compared to 9.07 of males. Ghomrassen in total has an illiteracy rate of 15.77.

Tunis: Sidi Hassine

Sidi Hassine is a town and neighborhood in the Tunis Governorate. As of 2014 it had a population of 109.672.

Sidi Hassine takes approximately 40% of Greater Tunis’s land area. It was once an agricultural area, but it has been overrun by anarchic houses.

Sidi Hassine, which is bordered to the west by the Sebkha and to the east by the Borj Chekir landfill, suffers from a proliferation of anarchic housing and multiple wastewater management shortcomings.

With an unemployment rate estimated to 16.47 and illiteracy rate of 15.61, the commune of Sidi Hassine is at a stalemate due to its lack of human capital and financial resources, as well as the lack of an effective executive apparatus. In the preparation of regional development projects, particularly waste recovery, it continues to rely on the central government.

Research subject

In this data collection phase, the research subjects are youth from the regions of Kasserine, Tataouine and Tunis with 3 specifics criteria mentioned below:

Age: Youth between 18 to 35 years old

Life experience: Youth who are originally from the targeted population and who experienced living in an included region of Tunisia (generally the costal side of the country)

Exposure: Participant must have been exposed to Jihadi and violent extremism groups propaganda either in person or on any online outlet.

Group discussion:

A focus group is a limited gathering of people that are demographically grouped to assess a current social or political phenomenon. Through this group interview, the participants are asked about their perceptions regarding their feeling of inclusion based on the 6 indicators concluded by the literature review. The focus group is an interactive process where the participants are free to express their point of views, in addition to interacting with other group members.

Through this research tool, the research team’s goal is to collect data about the level of exclusion and inclusion within the youth community in the different targeted areas in Tunisia.

The subject targeted in these focus groups are divided into two categories; the first consists of man and women between the age 26 and 35, while the second consists of young man and women between the age of 18 and 25. For each category 3 focus groups are conducted:

- One female-only focus group.

- One male-only focus group.

- One mix gender focus group.

Since the research focus on youth perception of inclusion in post-revolution Tunisia, the first category of 26 to 35 years old represents individuals who, as youth, lived in Tunisia before and after 2011, while the second category represents youth who grew in Tunisia post revolution.

The subjects in both categories, must have experienced both inclusion and exclusion within their lifetime. Participants are originally from City Ezzouhour in Kasserine, Ghomrassen in Tataouine and Sidi Hassine in Tunis (considered as excluded regions of Tunisia) and lived an experience in a considerate-to-be included regions such as the costal line of the country (either studied or worked in an included environment).

The focus groups are semi-structured; therefore, open to follow up questions to help the research team uncover the different aspects of the subjects’ experiences. Through these focus groups, the research team tested the perception of inclusion indicators among Tunisian youth.

Third Phase: In-depth interviews

In-depth interviewing is a qualitative research method that comprises conducting individual in-depth interviews with a small sample of respondents to learn about their perspectives on a certain topic, program, or issue. In our case, these interviews were conducted with 2 different categories. In a form of an open discussion to write participants life-stories, researchers focused on the Inclusion 6 indicators through follow up questions in order to depicts the interviewees perception.

Research subject:

The in-depth interviews were conducted with two different research subjects.

- Radicalized individuals

- Disengaged Individuals

No specific criteria were set to select the participants except their involvement with violent extremism either as supporter, participant, or ex-member of a violent extremist group.

Radicalized individuals

The first category is Tunisian youth who are radicalized. By radicalized we mean individuals who believe in the legitimacy to the use of extreme means in the achievement of certain goals, in our case the belief in the legitimacy of violence to achieve religious reign and install a political regime based on religion (Sharia law).

Interviewees are people who adopt an extreme belief system – including a willingness to employ, advocate, or facilitate violence – to achieve societal/political revolution through the success of the Sharia law.

We discover a dynamic of individuals breaking away from their local context at the heart of the radicalization process that leads to violence (family, friends, colleagues, etc.) as well as a trend toward radicalization that could lead to bloodshed.

As a result, violent radicalization is defined as:

- Adoption of an ideology whose logic becomes a true framework for a person’s life, activity, and meaning.

- The belief in using violent tactics to get one’s point across.

- The mash-up of ideas with violence.

The research team collected 6 life stories from 6 radicalized individuals.

| Interviewee | Gender | Age | Origin | Number of Sessions |

| Individual 1 | Female | 26 | Bizerte | 2 |

| Individual 2 | Male | 29 | Kasserine | 6 |

| Individual 3 | Male | 33 | Tunis | 5 |

| Individual 4 | Female | 33 | Tunis | 3 |

| Individual 5 | Male | 34 | Bizerte | 3 |

| Individual 6 | Male | 35 | Medenine | 2 |

Table 1 Details about the radicalized interviewees

Disengaged Individuals:

The second category consists of Tunisian disengaged youth. While de-radicalization is defined as the change in beliefs and mindsets that motivate extremist violence, specifically the belief that divine law must be imposed on others to save the world from corruption. This term is an umbrella term that describes why an individual changes their behavior and their beliefs.

Disengagement is ending the involvement with a violent extremist group. It entails a distinct behavior change, choosing to stop committing acts of political and ideological violence. This term was selected because it is an understudied phenomenon in the Tunisian context and still allows the team to examine radicalization process and the exit process of violent extremism distinguishing behavioral from cognitive in the process of deradicalization.

The research secured 5 disengaged Tunisian individuals’ life-stories. Although only two of them are in person, the three others are conducted through online calls knowing that these three are still based in foreign conflict zones more specifically in Libya and Syria.

| Interviewee | Gender | Age | Origin | Number of sessions |

| Individual 1 | Female | 24 | Sfax | 2 |

| Individual 2 | Female | 26 | Medenine | 2 |

| Individual 3 | Male | 29 | Kairouan | 3 |

| Individual 4 | Female | 32 | Tunis | 2 |

| Individual 5 | Male | 36 | Tunis | 4 |

Table 2 Details about the disengaged interviewees

In-depth interviews:

In this study, the research team, first, conducted in-depth interviews with Tunisian radicalized individuals that are supporting, advocating, and/or actively participating in national and foreign violent extremist groups activities,

In total, the research team interviewed 6 radicalized individuals 4 of them in person and 2 via online calls. While in some cases the in-depth interviews took 2 interview sessions, other took up to 6 sessions. Interview sessions lasted between 20 to 70 minutes.

Second, researchers run in-depth interviews with disengaged individuals, either used to support, advocate and/or have been part of violent extremist groups in Tunisia or abroad.

In total the study comprises 5 disengaged Tunisians aged between 24 and 26 years old and researchers conducted in-depth interviews that lasted between 2 to 4 sessions.

Relying on the expertise and the capacity of the researchers, for both categories, the discussion guide contains 4 questions to be discussed according to the interviewees flow of thoughts. However, the first in-depth interview session is restricted to ask the interviewee “How he/she feels?” The idea behind is to take all the necessary time to first gain the interviewee’s trust and to keep a dynamic discussion with follow up questions in interaction with the subject’s answers.

While in the next sessions, research have the freedom to reorder the following question depending on the respondent’s train of thoughts.

- How is/was work

- What he/she studied

- How she/he sees her/himself in the next 5 years

- How she/he sees Tunisia in 5 years

During the discussion, researchers’ follow-up questions included suggested probes—follow-up questions designed to explore specific aspects of an issue, in our case, explore the 6 indicators of the inclusion definition. In addition, issues may arise during the interview that could not have been anticipated, and interviewers can ask additional questions to find out more about relevant issues.

Data analysis:

The purpose of the analysis is to compare the perception of inclusion among disengaged/deradicalized individuals to the perception among non-radicalized and Radicalized Tunisian youth. This analysis will lead the research team to identify the key indicators that trigger the deradicalization process.

Focus groups:

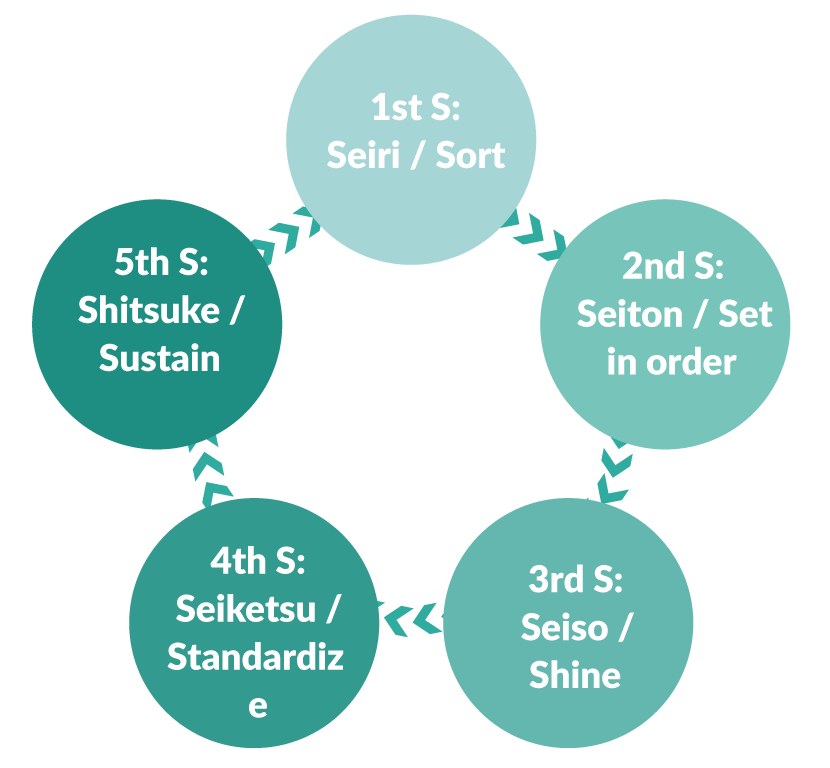

In defining youth perception of inclusion based on the literature review definition, the research team adapted the 5S method to the research context and applied it on the data collected from the focus groups.

The 5S method consist of employing 5 actions to the data with a continuous iteration in order to narrow down the findings:

- 1st S: Seiri / Sort

- 2nd S: Seiton / Set in order

- 3rd S: Seiso / Shine

- 4th S: Seiketsu / Standardize

- 5th S: Shitsuke / Sustain

Figure 3 The process of data analysis using the 5S methods.

In-depth interviews:

The transcript of each in-depth interview serves as the foundation for analyzing life tales. All of the stories are then organized into three levels (Demazière and Dubar, 1997): the level of functions (episodes of the story called sequences), the level of actions (elements of the story that stage Annotated “actants” (An), that is to say “characters”, who act, intervene, play a role in the trajectory) and the level of the narration (arguments and propositions noted (Pn) intended to convince the interviewee, to defend a point of view, to inventory the universe of possibilities).

Depending on the level the tale pertains to, each part is highlighted and commented accordingly. However, the same element might have several meanings.

The numerous parts from the tale are given in tables after the interviews have been completely sequenced. The data tables were used to sort the interviewee answers according to the 6 indicators defining Inclusion.

A comparative analysis between the life stories had been made to assess and validate the perception of inclusion among radicalized and disengaged individuals that the research is focusing on.

Data collection and analysis limitations:

The results of this study rigorously reflect the reality of the research subjects. They can also reflect the reality of other young people from the same populations. They provide indicators that can serve as a basis for measuring the impact of future interventions in the prevention of radicalization.

However, given the size of the sample relative to the young population in Tunisia, it will be very difficult to make an extrapolation for the whole country. It should still be remembered that this study concerns only the research subjects.

Data Access:

In the quest to interview radicalized individuals as well as disengaged Tunisian youth, the research team had to rely on personal connections and a long process of following leads and negotiating with organizations and/or individuals to access radicalized and disengaged Tunisians.

As expected, access to such research subjects was the most challenging aspect of the study. Due to security issues, the absolute secrecy of organized violent extremist groups and to lack of available data, the research ambition to interview a representative number of individuals, compared to the number of Tunisian jihadists, became unachievable.

Most leads to contact the research subjects and the interviews of radicalized individuals and returnees were interrupted either for security reasons or for lack of trust and in some cases, mainly with foreign fighters abroad, it was interrupted due to accessibility shortcomings.

In-depth interviews discussion:

When we study a subject as delicate and sensitive as the question of radicalization, there are no shortage of difficulties. One of the big difficulties was the reluctance of the interviewees to speak of their life experience. In the majority of cases, these individuals were expecting a criminal-investigation-like questions, believing they are dealing with agents of justice, adopt sometimes a posture of defense and denial of belonging to any jihadist organization. All these difficulties have been overcome thanks to the explanations provided on the scientific and confidential nature of the study.